When walking into any art museum in the Western world, there is a not insignificant chance for one to encounter artistic depictions of nudity. There is an even higher chance that the majority of these depictions are of female nude bodies, specifically.

Such was the case in the foyer of the MFAH’s Beck Building, where, when I was no more than eight years old, my elementary school class and I entered the museum for a field trip.

The sculpture closest to the entrance point; the art object that is first visible; the piece that visually and ideologically communicates that this is a fine art institution of great knowledge and cultural treasures—is a nude Venus sculpture. This Venus is partial, with only the torso intact. She is beheaded and dismembered, yet still presented for our perusal.

My classmates and I broke into giggles upon seeing this nakedness. We were rather promptly shushed.

Our teacher reminded us that artistic nudity isn’t wrong (the way non-artistic nudity is) and that many great works of art contain nudity. The other children and I looked up at this Venus, trying to understand how her naked body was different from those bodies deemed ‘inappropriate,’ and forbidden.

“It’s not sexual,” my teacher told us, “it’s art.”

That day, my female classmates and I learned that any discomfort we may feel, either from the ubiquitous objectification of the female form in art or from the reactions of our peers, was the mark of an unrefined palate and a mind not yet attuned to fine art. Nudity, we were taught, is the cornerstone of great art, and is in no way sexual.

Artistic female nudity is so common in our culture that questioning it seems reserved for the prudes of the world: those with inferior taste who couldn’t possibly appreciate or understand the refined technique and advanced composition and especially the metaphorical meanings of fine art.

As I was finishing my art history degree, this elementary school experience kept coming to my mind. The more I learned about art history as a discipline; the more I became familiar with formal conventions and their history; the more I considered what these art objects meant to their contemporary societies: I realized more & more that the presentation of artistic nudity as neutrally non-sexual was—to put it lightly—utter hogwash.

The partial Venus statue on display at the MFAH is a copy of Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos (c. 360-330 BCE). This artwork was the first significant work of Western Art to fully depict female nudity and was widely lauded as one of the sculptural masterpieces of the classical world. It is the nude from which all nudes are descended and is the blueprint that set forth the formal conventions that today make up the “nude.”1

The Knidian Aphrodite was also one of the first and most significant examples of erotic art in the ancient world and was an erotic tourist attraction in antiquity.

Pliny the Elder described the statue as “not only the finest work by Praxiteles but in the whole world,” and wrote that many visitors were so overwhelmed by the statue’s eroticism that they had to be stopped from masturbating in its presence.2 This tourism is further recounted by feminist art historian Catharine McCormack in her book Women in the Picture:

“Once they were alone in the sanctuary with the marble figure, one friend tried to kiss it on the lips, while the other, who was homosexual, went for her buttocks, claiming that they were as arousing as those of any young boy. The friends also noticed a stain on the statue’s thigh… [of which the priestess custodian explained] that a sailor had ejaculated on the statue when trying to have sex with it.”3

If you find this surprising, you’re not alone. Many art institutions, especially in the U.S., have discouraged (or outright denied) erotic readings of nude art: firstly via the doctrine that female nudity in art is an ‘appreciation of the female form;’ and secondly, in an attempt to assuage anxieties about the nature of this ‘appreciation,’ via the commonly repeated adage: it’s not sexual, it’s art.

This implies that for something to be a ‘great work of art’ it cannot be sexual in nature, and that sexualized depictions of nudity are not and cannot be ‘great works of art.’ This dichotomy also positions fine art in opposition to pornography to determine what sort of nudity is culturally appropriate. Interestingly, a few years before my school trip to the MFAH, the Child Internet Protection Act was passed, requiring institutions that receive federal funding to restrict Internet access to visual materials deemed obscene or “harmful to minors.”4

Why is showing a real picture of a naked woman to a minor illegal whilst taking children to see nude art at a museum permissible? Why is nude art—a literal objectification of women—held to such a different standard? Why do so many “great works of art” depict female nudity, and what is the purpose of such works of art?

To a modern viewer, especially one desensitized by hardcore pornography, a statue of Aphrodite bathing does not appear overtly sexual. As demonstrated above, however, contemporary Grecian audiences understood the Aphrodite of Knidos as being definitively erotic. The island of Kos, the temple to which Praxiteles first offered this statue, rejected it on grounds of obscenity and purchased a clothed version, whereas Knidos purchased the nude statue.5

In this essay, I intend to expose the reality that the Knidian Aphrodite and its resultant nude tradition are, very importantly, both sexual and art. It is crucial for us as feminists to reject this dichotomy and recognize the eroticized misogyny embedded in artistic depictions of women in Western Art.

To understand what the Knidian Aphrodite meant to contemporary audiences, we must return to the origin of both male and female nudity in Western Art: Classical Greece in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.

Ancient Greece had a thriving artistic tradition of “heroic male nudity,” referring to the armor-like physiques bestowed upon representations of Classical heroes.6 The Grecian religion and culture prized athleticism and displays of physical strength and dexterity in public festivals and games.7 The musculature of male nudes artistically represented the heroic virtue, or kalokagathia, meaning “beauty and goodness, conceived of as an inseparable pair,” of the subject.8

The Discobolus, sculpted by Myron of Eleutherae in the fifth century BCE, is regarded as one of the most influential pieces of Classical art ever made and is particularly lauded as a visual representation of kalokagathia.

Interestingly, the Discobolus’ abdominal musculature is anatomically incorrect.9 Despite the perceived accuracy of Classical sculpture, artists sculpted the body to display the subject’s character, not their appearance. To the Greeks, the male form was the pinnacle of human goodness, whereas the female form needed to be obscured in order to be ‘good,’ as Dr. Ian Jenkins, the British Museum’s curator and expert on Classical sculpture, elaborates:

“‘Representations of the naked male were common and I doubt they ever shocked anyone… [but] the fact is that in Ancient Greece social convention meant a respectable woman would never be seen unclothed.’”10

Chastity was the most important virtue for Athenian women. Respectable women were expected to wear a veil in public - on the rare occasion they left their house at all.11 Artistic representations of virtuous females, therefore, were always depicted fully clothed.

Female nudity first appeared in Classical art as sexualized depictions of courtesans (hetaira) or prostitutes (porne) painted on pottery.12 Ancient Athens had a thriving yet ambivalent culture of prostitution: brothels were state sponsored but prostitutes of all ranks were “not considered morally or lawfully worthy of sacred Athenian citizenship, marriage, or public ceremony.”13 Having sex with prostitutes allowed for Greek males to exercise their sexual superiority as virtuous democratic citizens and express their authority via penetration without impinging on the virtuosity of Athenian women.

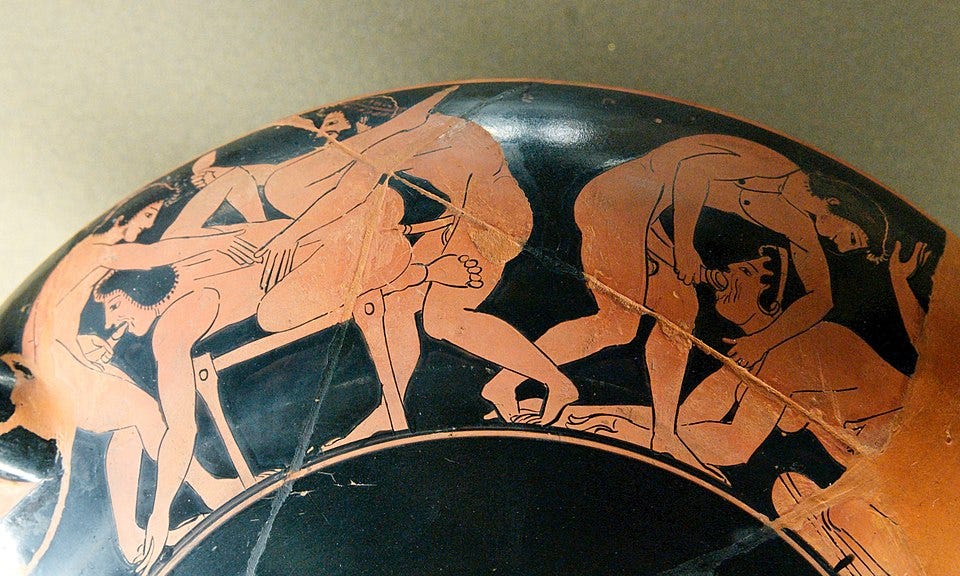

Artistically, prostitutes were depicted in unflattering ways that, by inverting kalokagathia, visually represented their poor moral character. This kylix, attributed to the Pedieus Painter (c. 475 BCE), depicts a group of active, young, male citizens engaged in sexual activity with a few passive, older, female prostitutes. The women are painted with cropped hair (a distinctive trait reserved for prostitutes), sagging breasts and bodies, and in demeaning, animalistic sex-positions.14

On the left side of this photograph, one of the men holds something in his hand over the woman. He is holding a sandal and beating her with it, as also implied by her hand cradling or protecting her ribs. The use of a sandal as hitting implement was a common feature of “erotic” vase paintings:

“The usage of the sandal in [erotic scenes] has been explained either as a means of sexual stimulation (presumably of the perpetrators) or to threaten, abuse, and intimidate the partner… who was in most cases a woman… the sandal embodies the power and control these males have over the prostitutes.”15

In Grecian culture, female nudity was a way to degrade the female body and enforce male supremacy. As previously described, however, the first significant fully nude female sculpture was not of a prostitute—but of a goddess.

Praxiteles created a new framework for understanding female nudity and sexuality, laying the groundwork for the conventionalized genre of nude art. However, Praxiteles’ innovation was not entirely divorced from the Grecian understanding of female nudity as an inherently erotic invitation for male sexual domination.

The Aphrodite of Knidos is a fully nude, freestanding sculpture in contrapposto position. She is hairless and flaccid, devoid of musculature or any sign of sexual maturity. Her genitals are modestly covered by her hand and the line of her bent arm leads the eye up to her abdomen and breasts. Her other hand clutches drapery that leads down to a bathing urn, both supporting the otherwise free-standing sculpture and telling the viewer that the goddess was undressing for a bath.

The inclusion of both a bathing urn and drapery is significant for multiple reasons: firstly, it humanizes Aphrodite by showing her engaged in a mundane activity. Secondly, it connects Aphrodite to her mythological origin of sea-birth—on the island of Knidos, Aphrodite was particularly invoked as a water goddess and given the epithet Euploia (fair sailing).16 Thirdly, it provided a moral context for the goddess’ nudity. As nudity typically denoted prostitutes, the bath setting made the goddess’ nudity socially acceptable.

By humanizing the goddess, however, Praxiteles allows societal views about nudity, patriarchy, and sexuality to color the interpretations of his sculpture. The inclusion of a bathing urn here becomes important for a fourth reason: Aphrodite clutching her robes transforms the nudity of this work from allegorical to literal: this formal component suggests that she has just disrobed. In other words, it suggests movement. It makes it real.

Unlike Classical examples of other cult statues, Aphrodite is looking to the side. She is unable to meet the viewer’s gaze and assert herself as an equal. To me, this brings to mind a formal convention deployed in paintings of prostitutes in which the male’s head and eyeline are higher than that of the females’, as a visual representation of female inferiority.17 Some scholars believe that Praxiteles modeled the Knidian Aphrodite after a courtesan he patronized, named Phryne.18 If this was the case, Aphrodite’s averted gaze and full nudity may be references to the artistic conventions typically used to denote a prostitute—contradicting interpretations of her nudity, pose, and bathing as purely mythological aspects.

The Knidian Aphrodite is a chimera of elements which both contain cult value and align its composition degrading and erotic conventions typically present in paintings of prostitutes. She is both ashamed of and calls attention to her nudity with the placement of her hand over her sex, adding mythological context (as Aphrodite was the goddess of sexual love and fertility) and an undeniable erotic charge. The bath setting provides just enough contextualization to preserve her virtue while also depicting a nude female body for the erotic pleasure of the male viewer.

While the original Knidian Aphrodite was lost to time, it spawned numerous extant copies, including the Roman copy we that now call the Medici Venus (pictured above). This Venus deviates from the Knidian original by adapting the grasping of robes into a covering of the breasts: the iconic venus pudica pose.

Similar to the Knidian original, the Medici Venus was famous for its eroticism. It was a popular stop on the Grand Tour, a pilgrimage to Paris, Venice, Florence, and Rome by upper-class European young men in the 17th to 19th centuries.19 This voyage served as the ultimate refinement of taste through the appreciation of art and culture—however, pilgrimages to see the Medici Venus and other ‘great works of art’ “were as much about admiring Italian masterpieces as they were an exercise in culturally sanctioned leering over images of the female nude body.”20

The mythological basis of nude art provides a moral context for privileged men to voyeuristically enjoy female nudity and reaffirm their social superiority: first over females as a sex-class; & secondly, over lower-class men. Ultimately, her mythological elements provide a moral pretense not for her to be nude, but for male citizens to look.

The Venus to end all Venuses, Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus serves as an example of how we define not only great art, but also great female beauty. When read through a feminist lens, however, this painting shows how nude art operates as a constructed other against which the patron/viewer can reinforce their patriarchal and individualistic worldview.

In art history, “nude” refers to an institutionally defined genre of painting. For something to be a nude, it must contain conventionalized formal elements of that genre—meaning that not all artistic depictions of naked humans are “nudes.” Crucially, for a work to be a “nude,” it must depict a female body in an eroticized state. This is because the formal elements that define the nude in Western Art rely on sexist formal conventions that place the female body in a subservient erotic role.

These elements intentionally erase any enthusiastic or real female sexuality, reinforcing that nude art’s eroticism is not reciprocal or productive heterosexuality, but the inability of the female body to escape such sexualization. Building from a framework outlined by Charmaine Nelson, the three primary formal elements are:21

The manipulation and/or erasure of body hair: nudes are almost always hairless, and any body hair present in a nude composition is relatively tame and groomed.

The location, position, and relation of the body to its environment within the art object: The nude as derived from Eve is often set in nature scenes. Moreover, Nelson argues that the nude is often arranged around phallic symbols. As this essay is intended for general audiences, I am spending the least time on this formal element. (Please read Nelson and/or Berger to learn more.)

The construction, activity, and composition of the body, face, and gaze: nudes are always passive, presented for the viewer’s perusal. Anatomical accuracy is less important than creating a sexually pleasing finished product. Nude subjects often have their gaze averted; when they do meet the viewer’s eye, their gaze is soft and expression is inviting. She invites the male viewer to look.

The venus pudica pose, here deployed in painted form by Botticelli, is one of the primary conventions used to transform a naked body into a “nude,” and exemplifies the final listed convention. In this pose, the shameful modesty of the female subject trying to cover herself is contrasted with the voyeuristic gaze of the artist, patron, and viewer. Shame is never placed upon the male voyeur; female nudity is freely presented to be ravenously dissected by his gaze. After all, pudica comes from the Latin term pudendus, meaning both shame and vulva.

In his BBC teleprogramme Ways of Seeing, art historian John Berger proposes the following distinction: 22

To be naked is to be oneself.

To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself.

A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude. (The sight of it as an object stimulates the use of it as an object.) Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display.

To be naked is to be without disguise.

To be on display is to have the surface of one's own skin, the hairs of one's own body, turned into a disguise which, in that situation, can never be discarded. The nude is condemned to never being naked. Nudity is a form of dress.

In Botticelli’s example, the female model’s individual identity has been replaced by the traditional appearance of Venus, fetishizing her femaleness and reducing her down to her sex. Female sexuality and reproductive capability is an enduring source of anxiety for the male ruling class. In an effort to assuage this anxiety, nude paintings developed formal conventions that disguise female sexual maturation.

Importantly, most Venuses (including Botticelli’s and Praxiteles’) lack body hair. Visually, this represents the male desire for a youthful, easily controlled sexual partner. A lack of body hair suggests a prepubescent female body—one without agency or worldly knowledge.

In the case of Venus, however, her lack of body hair and covered genitals comfortingly remind the viewer that they are not looking at a real woman, but at a representation of male desire.

This is not unique to Botticelli or Praxiteles or any male artist who has deployed Venus imagery. It is a fundamental aspect of the Venus myth itself. In Classical mythology, Aphrodite/Venus functioned as a male-created representation of ideal female sexuality. She was born not from a womb, but from the severed genitals of Uranus that were thrown into the ocean:

“where they frothed and transformed into a beautiful woman who was a goddess of love, beauty, and fertility…. The enduring Western symbol of feminine beauty and sexuality [came from] the sex organ of a man. Venus [Aphrodite] is the butchered testicle of her father’s body.”23

The prototypical mother of Western female beauty and sexuality, the ultimate representation of sexuality and desire, is not a female at all. She was spawned from the reproductive organs of a male. She exists independent of female reproductive capability as it exists in reality.

Crucially, The Birth of Venus does not actually depict Venus: it is, rather literally, a painting of a nude female model who posed for Botticelli and his workshop in the late fifteenth century to fill a commission by a wealthy male patron for the purpose of erotic pleasure. It may have even served as a sexual guide for the patron’s young and often inexperienced sexual partners, as was the case with Titian’s masterpiece, the Venus of Urbino, which Mary Beard here describes in her Shock of the Nude special:

“But for me, it’s hard to forget that this is a naked woman painted by a male painter for a male buyer or commissioner. You have to imagine him standing here, meeting her gaze, probably titillated by whatever the hand is doing. It’s hard, really, not to see this painting, like so many other, similar European nudes, as one of a passive, naked woman being the object of an erotic male gaze.”24

Venus is a fabricated representation of male heterosexual desire and divorced from real female sexuality that has been used to support, perpetuate, and naturalize the sexual objectification of women in Western culture. The female nude, as it has derived from Venus, must be fundamentally understood not as an accurate representation of female nakedness and an appreciation of female sexuality, but as a culturally constructed artistic tradition that depicts women as erotic objects.

Moreover, male artistic creation is a part of the economic and legal system of patriarchy, a system of sex-based oppression that is upheld with cultural beliefs, moral values, and artistic expression. The ubiquitous subject in Western art and the paradigm for female beauty has therefore been almost entirely conventionalized, commissioned, and created by male artists and patrons.

In “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (1971) feminist art historian Linda Nochlin explains how mastery over anatomy, gained through life drawing, is one of the markers of a ‘great artist.’ Until the 20th century, however, female artists were barred from entering life drawing classes, creating an institutional barrier to their mastering of anatomy and the creation of ‘great works of art.’25

Furthermore, the very concept of a great work of art presupposes the existence of a great artist: and to be a great artist is to possess the internal essence of “genius.” This concept, described by Nochlin as the “gold nugget theory,” serves not only to obfuscate the societal and material conditions that produce great artists and their art but to culturally reinforce the idea that greatness, especially male greatness, is due exclusively to individual merit and achievement. This ideology is self-perpetuating: if “genius" and “greatness” is contained within the individual, then individuals (and demographic groups) who do not achieve greatness have only themselves to blame.

This inequality was famously highlighted by the Guerrilla Girls, first in 1989 (pictured below), then again in 2005 and 2012. The 2012 reissue has updated the number of women artists to be less than 4% and female nudes as 76%.26

Interestingly, this implies that the museum did not acquire more work by female artists, but instead acquired more male nudes. As previously demonstrated, however, male nudes have historically functioned as a heroic power fantasy (or in the modern era, as gay erotica), whereas female nudes have functioned as sexual objects that encode misogynistic views of women.

Nude art (and all Venus imagery) therefore contains a layered ‘male gaze’:27 the female model is posed and directed by the male artist; represented via the art object in ways that will best please the male patron; who can then use the object for his own, usually erotic, means. Such was the case for the Rokeby Venus’s most famous owner, J.B.S. Morritt, who

“wrote to his friend Walter Scott in 1820 describing how its position above the fireplace made for a flattering play of light on Venus’ painted buttocks and observed how the picture made women feel uncomfortable.”28

Women are bombarded with objectified imagery of their sex relentlessly since birth. They are, by and large, not oblivious to what formally constitutes erotic imagery. This is precisely why it is so alienating and dehumanizing to mystify the nude as a tradition of non-sexual great art—it naturalizes the submissive and sexually pliant nature of women depicted by male artists.

The nude serves as a cultural representation of male superiority - social, sexual, and artistic - and female inferiority in those same areas. When combined with the deeply ingrained social, cultural, and legal patriarchal subjugation of women on the basis of their sex, the public exhibition of nude art expands this ownership role from the previously exclusive patron and social circle setting into the inclusive ownership of all male visitors to the gallery.

Furthermore, the erotic function of the nude is hidden by the pornography-art dichotomy, in which an object cannot simultaneously be both pornographic and artistic. As evidenced by the visual comparisons offered by Berger in Ways of Seeing, however, there is little formal deviation between pornographic photography and nude art.29 The formal similarities between pornography and nude art reveal a deeper truth: that the nude serves as the formal and ideological basis from which modern hardcore pornography has sprung. Pornography is to the nude as television was to the photograph: inevitable.

We cannot even be shocked or disturbed at the increase of problematic pornography use within a generation that was shown erotic and misogynistic imagery of nude women through the guise of art or culture and told it was devoid of sexuality. This serves to naturalize the sexist conventions present in the nude and up the ante in regards to what is read as erotic.

The pornography/fine art divide places the burden of vulgarity on the viewer who dares to comment on the rather obvious erotic content—only for that viewer to be shamed for their sinful interpretation of an otherwise chaste art object. This ultimately reinforces the cultural conception that women exist in an essentialized state of sexual subservience, and that the female body exists for male sexual fulfillment and scopophilic delight.

To dissolve the pornography/fine art dichotomy, counteract the naturalization of sexist stereotypes, and increase public artistic and historical literacy, I argue the following:

First, I argue against the public, all-ages display of nude art. I believe that all nudity should be treated equally and that subjective assessments of “artistic quality” or “cultural importance” should be by and large irrelevant.

I believe that all nude art—male, female, heroic, erotic, naked, nude—should be treated as “sensitive material” and only be displayed in optional, partitioned galleries that visitors can choose to enter. Labelling these galleries as having ‘adult sexual content’ and recommending only adult visitors enter will allow school groups, families, and other mixed-age groups to act at their own discretion.

Moving nude art into a partitioned gallery may also bring attention to the voluntary action of the visitor to enter the ‘nude gallery.’ Making visitors choose to view nude art places them in the role of the voyeur and highlights their desire to look. This may function similarly to Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés, in which each viewer must go up to the assemblage and “peep” through the hole in order to see the reclining nude presented within.

Secondly, I argue that any display of nude art must be properly contextualized. This information must be provided in tandem with the display of such art.

Due to the ubiquity of hardcore pornography, contemporary culture of extreme sexist imagery, and the naturalization of artistic nudity by museums and other ideological state apparatuses, I do not believe that the average museum or gallery visitor is able to accurately discern erotic and sexist content within a majority of nude art objects. It is negligent on the part of the institution to present these sexist, eroticized depictions of women without contextualization that counteracts ideological naturalization of the patriarchy.

I believe that the best way to do this is with in-exhibition didactic text, artwork labels, and supplemental information resources (QR codes, iPads/kiosks, pamphlets, etc.). As for institutions that typically omit wall text—I question if the aesthetic value of a white cube outweighs the ideological harm of naturalizing sexist depictions of women.

This extends to the contextualization of non-sexual nudity, such as heroic male nudes and ‘nakeds’ of either sex. By clearly highlighting which examples of artistic nudity function as erotica and which do not, each viewer will be familiarized with the conventions used to denote a “nude.”

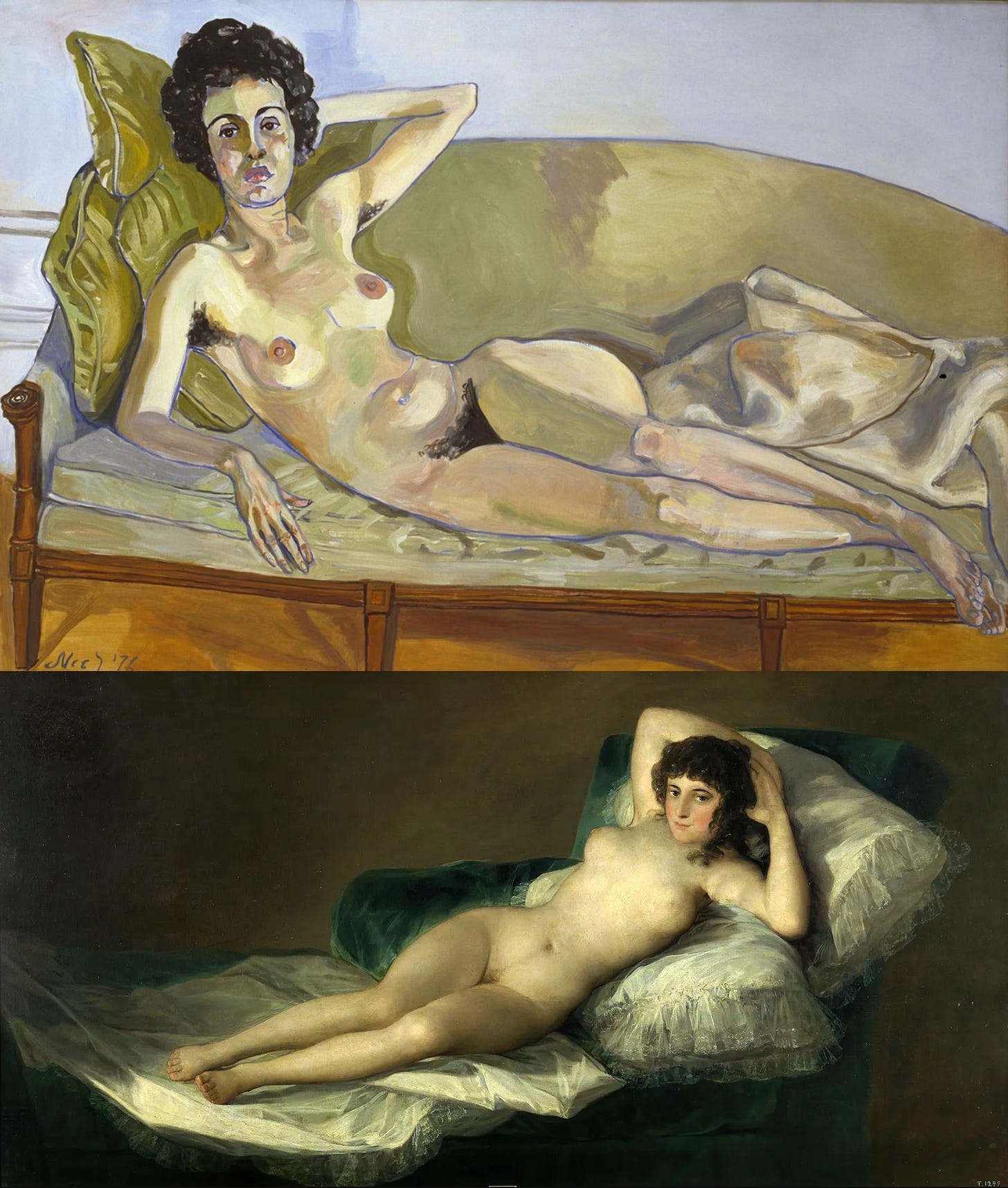

As an example, compare these two paintings:

Now consider the following context:

Above is a 1978 painting by Alice Neel. It was created during the filming of a documentary on Neel by feminist filmmakers Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes. It is of documentarian Lucille Rhodes and was composed in Neel’s studio with only Murphy, Rhodes, and their cinematographer (also female) present. (Watch the documentary or read this interview with Murphy and Rhodes for more information!)

Below is the compositional model that Neel adapted for her nude: La maja desnuda, created in 1797-1800 by Francisco Goya. The identity of the model has been lost to time, but the painting was most likely commissioned by Manuel de Godoy, who displayed it in a private room full of other ‘Venuses’ (or, as already established, nude young women).30

The bottom composition was first and foremost intended to erotically titillate the male patron/viewer, whereas the top composition is a naked portrait created during a filming of a female-created documentary featuring a female artist. It is a portrait, not a nude. Conversely, the above work does not depict a woman—it depicts Venus.

By presenting this information, the viewer is easily able to discern not only the formal differences between these paintings, but what those formal differences mean.

This brings me to my third and final argument: I propose a restructuring of arts education that considers the extensively described “nude problem.”

In this essay, I have clearly demonstrated how the formal conventions that create the female nude are rooted in sexist ideology & how, from its inception, the primary purpose of female nudity in art was to provide erotic titillation to the male patron/viewer. I do not believe that sexualized depictions of women are appropriate for children, regardless of “artistic mastery.” There are many examples of artistic mastery that do not contain explicit sexual content and the potential harm of showing erotic material to children outweigh any potential benefit. I believe that artistic nudity has little place in a standard K-12 education. (This is excluding 9-12 level art or art history classes.)

What is to be done, however, about art historical education? As the ubiquitous subject in Western art, the nude cannot easily be disentangled from the canon.

As any recent art history graduate will tell you, however, the canon has become bloated and in many ways, irrelevant. Recent efforts to diversify and expand the canon have rendered it—as an inherently exclusionary cultural lineage—largely obsolete.

I believe that the art history survey class should instead focus on the fundamental skills and methods that are required for the discipline: visual analysis, object-based research, and writing art historical essays. I argue against the continued teaching of the ‘canon’ and the un-critical inclusion of nudes in art historical survey classes and texts. The topics of both the canon and the nude are best suited to specialized, upper-level art history courses.

While my arguments are radical, I hope that this essay has equipped you, dear reader, with enough historical, artistic, and feminist context to better navigate images of nudity and images of women you see in your own life.

Kousser, R. “The Female Nude in Classical Art: Between Voyeurism and Power,” in Aphrodite and the Gods of Love, edited by C. Kondoleon & P.C. Segal. MFA Publications, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2011. https://www.gc.cuny.edu/sites/default/files/2021-12/Kousser_AphroditeMFA2011.pdf

Bellis, A. “A Roman Statue of Aphrodite on Loan to The Met,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 9, 2023, revised November 5, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/roman-statue

McCormack, C. Women in the Picture: What Culture Does With Female Bodies. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. 2021. (p. 35)

Thornburgh, D. “Youth, Pornography, and the Internet.” Issues in Science and Technology, 2004, Vol. 20, No. 2 (WINTER 2004), pp. 43-48. http://www.jstor.com/stable/43312427

Bellis, A. “A Roman Statue of Aphrodite on Loan to The Met,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 9, 2023, revised November 5, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/roman-statue

Herring, A. "Pottery, the body, and the gods in ancient Greece, c. 800–490 B.C.E.," in Reframing Art History, Smarthistory, July 21, 2022. https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/pottery-body-gods-ancient-greece-early/.

Sorabella, J. “The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, Jan. 2008. https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/the-nude-in-western-art-and-its-beginnings-in-antiquity

Kousser, R. “The Female Nude in Classical Art: Between Voyeurism and Power.” (p. 149)

Beard, M. “The Shock of the Nude,” BBC television programme, uploaded on YouTube. youtube.com/watch?v=1YzlsNyEvm8 (25:35)

Dowd, V. “British Museum defines Greek naked ideal,” BBC article, March 31, 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-32120302

Beard, M. “Women in Power,” London Review of Books Lecture, uploaded to YouTube March 8, 2017. youtube.com/watch?v=VGDJIlUCjA0 (18:45)

Tulloch, J. H. (Editor). A Cultural History of Women in Antiquity, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015. ISBN: 9780857850973 (p. 42)

Beck, M. L. “The Representation of Prostitutes in Ancient Greek Vase-painting,” Kennesaw State University, Proceedings of The National Conference On Undergraduate Research (NCUR) 2016. https://libjournals.unca.edu/ncur/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/1938-Beck-Madeline-FINAL.pdf (p. 1847)

Beck, M. L. “The Representation of Prostitutes in Ancient Greek Vase-painting.” (p. 1848)

Young, Y. “A painful matter: the sandal as a hitting implement in Athenian iconography,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. The Open University, Israel. 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343609517_A_painful_matter_the_sandal_as_a_hitting_implement_in_Athenian_iconography (p. 5-6)

Kousser, R. “The Female Nude in Classical Art: Between Voyeurism and Power.” (p. 150)

Beck, M. L. “The Representation of Prostitutes in Ancient Greek Vase-painting.” (p. 1848)

“Praxitele,” Louvre, https://mini-site.louvre.fr/praxitele/html/1.4.6_en.html

Sorabella, J. “The Grand Tour,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 1, 2003. https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/the-grand-tour

McCormack, C. Women in the Picture: What Culture Does With Female Bodies. (p. 36)

Nelson, C. “Coloured Nude: Fetishization, Disguise, Dichotomy.” RACAR: revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review , 1995, Vol. 22, No. ½ (1995), pp. 97-107. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42630539

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. https://www.ways-of-seeing.com/ch3

McCormack, C. Women in the Picture: What Culture Does With Female Bodies. (p. 42-43)

Beard, M. “The Shock of the Nude.” (12:16)

Nochlin, L. “Why are there no great women artists?” Originally pub. 1971. Accessed via https://www.writing.upenn.edu/library/Nochlin-Linda_Why-Have-There-Been-No-Great-Women-Artists.pdf

“Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?” Artwork by Guerrilla Girls, via https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/849438

Mulvey, L. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Film Theory and Criticism : Introductory Readings. Eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford UP, 1999: 833-44. (Originally written 1975.)

McCormack, C. Women in the Picture: What Culture Does With Female Bodies. (p. 42)

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. https://www.ways-of-seeing.com/ch3

Museo del Prado, La maja desnuda. https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-naked-maja/65953b93-323e-48fe-98cb-9d4b15852b18

This puts many thoughts I've had about 'nonsexual' nudity into words, especially as a female CSA victim. When you're exposed to hardcore sexual depictions of nudity from such a young age, it becomes hard to divorce nudity from sexuality, and the narrative of this art feels alienating. Nudity itself isn't inherently sexual, and we've been told this over and over, yet that entirely ignores the history of these pieces. In a vacuum, it's possible to have nonsexual nudity, but there's a reason we don't find female depictions of naked heroism. I wish there was genuine mundane nude art, with unflattering poses in a way that isnt directed at the viewer. Not with the intent of making something ugly, but out of relatability and humanity. Women should be able to see themselves in art, not just see who men think they should be.

whoa you changed my life with this. super interesting i always vacillate between nudity being sexualized vs liberating but whichever it is it is so crazy that male bodies are not! really well written!!!